The problem with UK public sector pensions is that they are a Ponzi scheme, and were more or less identified as such in the report by the Public Sector Pensions Commission published in July 2010. The reason for this is that, unlike private or personal pension plans, where the contributions of employees and their employers are invested in individual, ring-fenced, and gradually accumulating pots of money, in the case of public sector pensions no such separate and identifiable funds are ever established or built up. Instead, the pensions of today’s public sector retirees are paid directly out of the contributions made by current public sector workers: a system or model which continually requires the recruitment of new contributors to underpin the pyramid, and which, when applied in a related financial sector, earned Bernie Madoff a sentence of life imprisonment.

Of course, Bernie Madoff knew what he was doing; whereas it is possible that those who originally devised our public sector pension schemes may not have seen the dangers. For during the first few years, when there were yet very few public sector pensioners and a growing number of public sector workers, most of the schemes would have almost certainly been in surplus. From the point of view of the treasury, in fact, employee contributions would simply have been regarded as an additional form of tax: a helpful source of revenue which would have continued to grow throughout the 60s and 70s as health and education and other public services continued to expand. The trouble is that all those people who entered public service during this period of rapid public sector growth are now of pensionable age; and with us all living much longer, the pensions they are receiving far exceed the contributions being made by their successors. As a result, the bulk of these pensions are now having to be paid by the rest of us, out of general taxation.

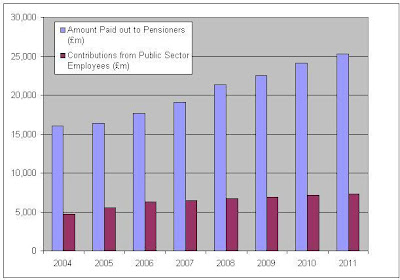

How much we are actually paying can be seen in Figure 1, which is based on data provided in the above-mentioned 2010 report, and which can be found in PDF format at http://www.public-sector-pensions-commission.org.uk.

Figure 1: Growth in Public Sector Pension Deficit

In the report, the numbers are actually presented in a way that is slightly more complicated than this, in that part of the deficit is notionally deemed to be made up by the employer. This, however, is a polite fiction. For while the ‘employer contributions’ deducted from the NHS budget, for instance, may relate to the numbers of staff currently employed, they are actually used to pay the pensions of doctors and nurses who have already retired. This also explains why these notional ‘employer contributions’ have become so disproportionate. In the case of civil servants, for instance, the ‘employee’ contribution is just 3%, while the contributions of the various government departments to which they are assigned has risen to a massive 24%. This, however, is merely a way of disguising the current account deficit. And even then, additional monies are still having to be paid directly out of the treasury.

What is even more important, however, is the fact that, as one can see from the above graph, the deficit is steadily growing: from £11.4 billion in 2003/04 to an estimated £17.95 billion in 2010/11. That is an average annual increase of 4.6%. And the question we therefore have to ask is how big this funding gap is likely to get.

Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be anyone who actually knows the answer to this question. Or if they do, they’re not telling us. Nor is it all that easy to work it out. For the only figures available which even touch upon this issue are for the total public liability as it stood at the point at which the liability was measured. That is to say that they tell us how much we would be contractually obligated to pay present and future public sector pensioners if the schemes to which they belong were otherwise suspended, with no further contractual obligations being incurred. They do not tell how much these contractual obligations will continue to grow as the schemes themselves go forward. In this sense they are not forecasts; merely statements of account. They are also snapshots, taken at a single moment in time, which are almost immediately out of date. Indeed, the most recent such snapshot I have so far been able to find – included in the above mentioned report – is an estimate of what the total liability stood at as of 31st March 2010, when it was believed to be £1.176 trillion. Since then, however, it will have already grown substantially.

Not that we are going to be asked to pay this off over night, of course. As in the case of treachery bonds – which, in the light of this £1.176 trillion, constitute only our second largest category of public debt – the pension liability is spread over a fairly large number of years. Unfortunately, the Public Sector Pensions Commission’s report doesn’t tell us how many. Nor does it give us a profile of how the liability will be discharged on an annual basis. All we can say for sure, therefore, is that it won’t be linear. For although the liability, as presented in the 2010 snapshot, takes into account not only current pensioners, but all those who are currently building up an entitlement – including those who have only just started on this process – as already stated, it measures their entitlement as it stands today, not as it will stand at the end of their working lives. If we were to create an annualised payment profile for the £1.176 trillion current liability, therefore, it would probably look something like Figure 2.

As you can see, this profile has a fairly long tail. This is because the people who will still be receiving pensions in the 2080s are those who would have only just started work when the snapshot was taken. It is their entitlement at that point, therefore, rather than the entitlement they will eventually build up, that the snapshot reflects. In reality, however, most of these people will go on to receive full pensions, and far from tailing off, the liability will therefore continue to grow. In fact, it is unlikely even to peek during this time frame. For even if the number of people retiring on public sector pensions were to remain constant – rather than continue to rise as is currently the case – the increase in life expectancy – and hence the number of years each pensioner draws a pension – would ensure that the cost continued to rise. In order for the liability merely to plateau, therefore, the number of people retiring on public sector pensions would have to fall. This, however, would mean that the number of people working in the public sector would also have to be reduced, which, of course, would have the further effect of reducing contributions. Like all pyramid selling schemes, in the end it is simply unsustainable.

Given the generous nature of public sector pensions, and the fact that they are being paid for by tax-payers who, for the most part, cannot afford such pensions for themselves, it is also indefensible.

Of course, apologists for the system will argue than rather than reducing public sector pensions or making them less generous, private sector pensions ought to be brought up to the level of the public sector. This, however, is economic fantasy. Most, if not all, companies which created final salary pension schemes during the 1950s, copying the public sector model, have now abandoned them, or have gone out of business, partly as a consequence. One of the reasons the previous government couldn’t save MG Rover, for instance, was that no one wanted to buy a company with such a huge pension liability. We therefore have to accept that the only way we can provide pensions for ourselves is by saving money into a pension fund, out of which an annuity can eventually be bought. The problem is that, even with contributions from one’s employer, there is a practical limit to how big a pension fund most of us can build.

Assuming an average return on investment of 7% per annum, for instance, someone on average pay, who had a pension plan in which both he and his employer had paid in 5% of his salary per year for the last thirty years, would now have a fund worth £167,000. If we take a fairly typical annuity purchase rate of £5,972 for every £100,000 invested, this would give the average retiree a pension of £9,973 per annum at the age of 65.

To demonstrate how unfair public sector pensions are, someone on an identical salary in the public sector would get a pension of more than double this, and at the age of 60 rather 65. To get an equivalent pension, in fact, the person in the private sector, together with his employer, would have to make a combined contribution of 21% of his salary per year. For the vest majority of people in this country, therefore, this is simply not possible. Yet it is this majority – the 22.9 million people who work in the private sector – who are paying for the public sector pensions of the privileged minority.

What is truly remarkable, however, is that when public sector workers went on strike last week to protest against the government’s proposed reforms, the majority of people – between 63% and 68% depending on which opinion poll you read – actually supported them. It is another example, in fact, of what I have referred to in the past as the strangely inverted political culture we have in this country: one which tacitly assumes that the Labour Party and the trade unions, like latter day Robin Hoods, are on the side of ordinary working people, while the Conservative Party, like the wicked Sheriff of Nottingham, is a bunch of callous, uncaring tyrants, determined to grind poor public sector workers into the dirt. What makes this perennial caricature even less apposite on this occasion, however, is how moderate the proposed reforms clearly are.

I say this because the one thing the government is certainly not proposing to do is put an end to the real underlying problem of public sector pensions: their fundamental pyramid structure. For that would mean placing the notional contributions of both employer and employee into real pension funds. While still having to meet the contractual obligations of existing pensions, this would mean that they would not be able offset current pension payments with these notional contributions, thus widening the pension deficit and further adding to overall borrowing. Over time, they would also have to augment or consolidate these new pension funds with the contributions that should have been paid into them in the past, along with the interest they would also have been earning. The cost would be astronomic. All the government is actually proposing, therefore, is to (a) bring the retirement age for public sector pensions into line with the state pension age – which, reducing the number of public sector pensioners at any one, would relieve some of the burden in the medium to long term – and (b) increase present employee contributions by 3%, thus reducing the current pension deficit.

The fact that it is this latter proposal which has caused the greatest resentment, however, is a clear indication of how entangled in deception and delusion the current situation has become. For most public sector workers almost certainly know that their so-called contributions are not actually contributing to their future pensions. They know that they are simply an additional tax, which they have every right to suspect the government is merely levying in order to reduce the overall fiscal deficit. On the other hand, they refuse to accept the corollary of this: that their pensions are entirely paid for out of taxation, most of which is collected from other people. The problem is that while both sides, for various reasons, continue to maintain these polite fictions, it is difficult to see how the dispute can be resolved.

There is also another reason why we need to stop deceiving ourselves and face up to the truth. For the world economic order which, for last thirty years, enabled the mature western democracies to consume more than they produced, spend more than they earned, and pay for it all on tick, is coming to an end. In 2008, the bubble finally burst. Public sector pensions were both a symptom and a contributor to what was wrong with our economy throughout this thirty year period. If we go on arguing about them from entrenched political positions which are no longer relevant, we are not going to solve the problems. The western democracies that will come through this crisis most intact will be those that stop deluding themselves, face up to the truth and start finding new ways to live, work, and structure their economies to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Reliving the political battles of the post-war period will not do that. We need fresh thinking and a fresh approach, based on economic reality. For if we fail, our children and grandchildren will be paying the price for decades to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment